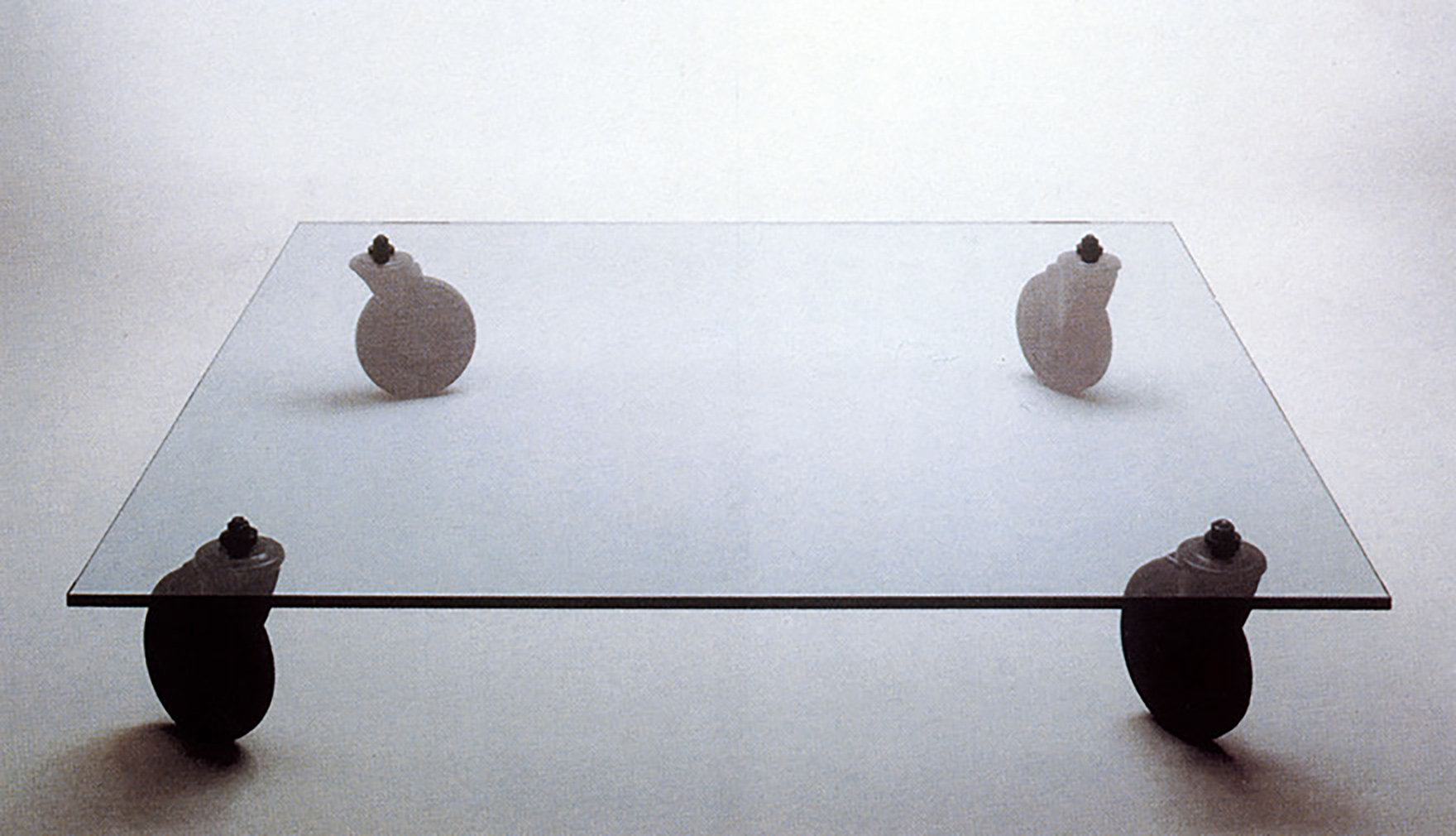

I. Gae Aulenti

Aulenti’s 1993 Tour table for Fontana Arte

Gae Aulenti — Born in Palazzolo dello Stella, Italy, 1927. Died in Milan, 2012.

“[A]rt exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony. The purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known. The technique of art is to make objects ‘unfamiliar,’ to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged. Art is a way of experiencing the artfulness of an object: the object is not important.” —Viktor Shklovsky from Art as Technique, 1917

The subject of the above quote by Viktor Shklovsky is poetic language, and the subject of our brief essay is the architect and designer Gae Aulenti. Admittedly, “poetry” and “poet” have almost become useless terms. In our age, to call someone a poet seems either anachronistic (like, “Oh, they’re still doing poetry?”) or vague, like one is weakly praising some indistinct whiff of beauty. “Poet” and “poetry” clearly need some scrubbing and recalibration. Obviously, the word’s main connotation is a practitioner of the literary sort, but it would be valuable to expand it, and stabilize it, to mean something like: those who make objects of communication, and whose main material for these communicative creations is poetic language — whether imagistic, textual, sculptural, or what have you. In light of this attempted definition, Gae Aulenti was a great poet.

Aulenti studied architecture at the Milan Polytechnic. After graduating she worked at Casabella magazine from 1955–65 under Ernesto Nathan Rogers. Although she was a graphic designer at the magazine, she completely absorbed Rogers’s architectural tutelage — saying later that Rogers was the most significant influence of her life. The influence is clear, and his Torre Velasca is a great example; the building (designed with his Milanese firm, BBPR) is highly idiosyncratic and elegant, and almost all of Aulenti’s work has this particular, uncommon charm. Throughout her career she was a very successful industrial designer, originating many pieces for Knoll, Zanotta, Kartell, Artemide and other companies. Most of Aulenti’s architectural commissions were for museums (the Musée d’Orsay, the Pompidou Center, the San Francisco Asian Art Museum), and Aulenti was one of only a few major female architects in Italy in that era. When asked if being a woman affected her practice, she simply replied “yes.”

Left: the Pipistrello lamp for Martinelli Luce (1965). Right: Rimorchiatore, a combined candleholder, vase, light and ashtray (1967.

Left: the Pipistrello lamp for Martinelli Luce (1965). Right: Rimorchiatore, a combined candleholder, vase, light and ashtray (1967. The Jumbo coffee table for Knoll International (circa 1965)

The Jumbo coffee table for Knoll International (circa 1965)In the 1960s and early ’70s, Aulenti was part of a loose international network of radical designers and architects, including the likes of Superstudio, Ettore Sottsass, Gruppo Strum, Hans Hollein, Archizoom, Ant Farm and many others. This web of progressives was perhaps best represented by MoMA’s seminal 1972 show Italy: The New Domestic Landscape. The tone of the exhibit clearly and distinctly promoted the theoretical, neo-science-fictive atmosphere of the time. Although Aulenti contributed much to this speculative era, the core of her work had zero utopian conceits; she made consciously provisional objects and environments, and she was aware of the untenable nature of any future predictions. “If I now look at the lamps I made, I never see them as machines for producing light,” she said. “They are forms suggested by the work that I was doing in that moment for a particular space, so they went there first and then they went into production; they went to an entirely new destiny.”

Victor Shklovsky wrote that “The technique of art is to make objects unfamiliar...” The overlap between this notion and Aulenti’s work is quite incredible; what better could be said when looking at Aulenti’s Pipistrello lamp or her Jumbo coffee table? Neither are not a coffee table or not a lamp but strange versions of these objects. As with much of her work, there seems to be a “roughening” of design language — not an abstracting, not a proposition, but an attempt to “impede” or “slow” the actual perception of the designed object. (These last quoted verbs are taken from a further section of Shklovsky’s essay; he writes, “The language of, poetry is, then, a difficult, roughened, impeded language.”)

Above and below: La Grotta Rosa on the Amalfi Coast (1969–72)

Above and below: La Grotta Rosa on the Amalfi Coast (1969–72)

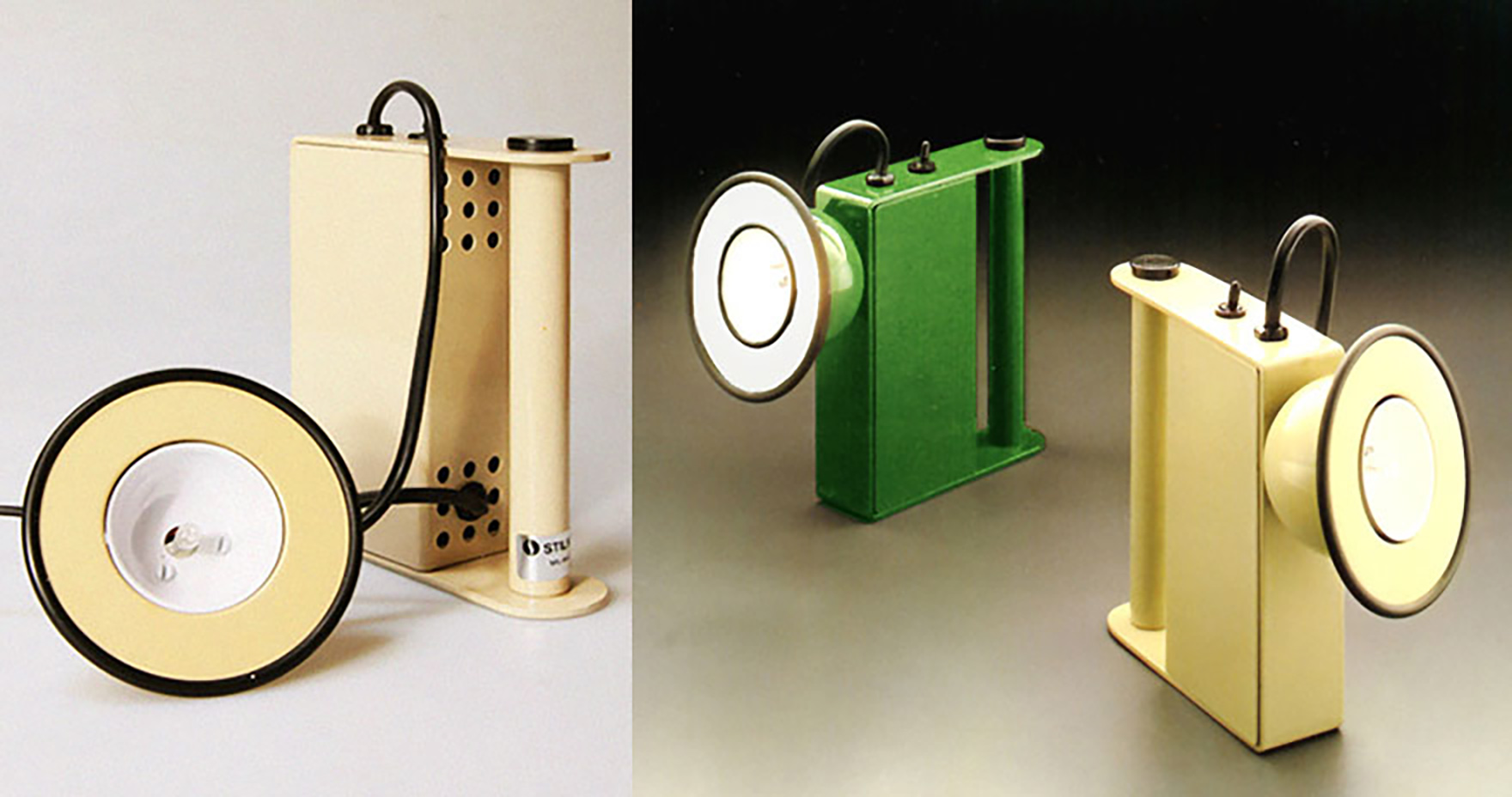

The Mini Box Stilnovo table lamp (1981), by Aulenti and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni

The Mini Box Stilnovo table lamp (1981), by Aulenti and Pier Giacomo CastiglioniIn 1979, Aulenti gave an interview to Franco Raggi that provides further insights into the depths of her understanding. In particular, she expressed concern about how some architects, through a kind of “solipsistic” theorization, misinterpret the nature of a built structure (or design): “Sometimes people speak about reality as if a field effectively existed where it is expressed. Instead realities are infinite...” Here and elsewhere in the interview, Aulenti seemed to be saying that when one introduces a piece of design or a piece of architecture, not only is the “reality” of the designer or architect not of utmost importance, but the creation will be received by endless sensibilities.

Poetic language is a type of language among others: the language of the tyrant (whether domestic or political), the language of masculine and feminine, the language of architecture, the language of capitalism, and on and on (and of courselanguage, like “realities,” is infinite). But it is the language of the poet that has the most importance, perhaps because it is language itself, in all its glorious inscrutability, and not something pointing elsewhere.

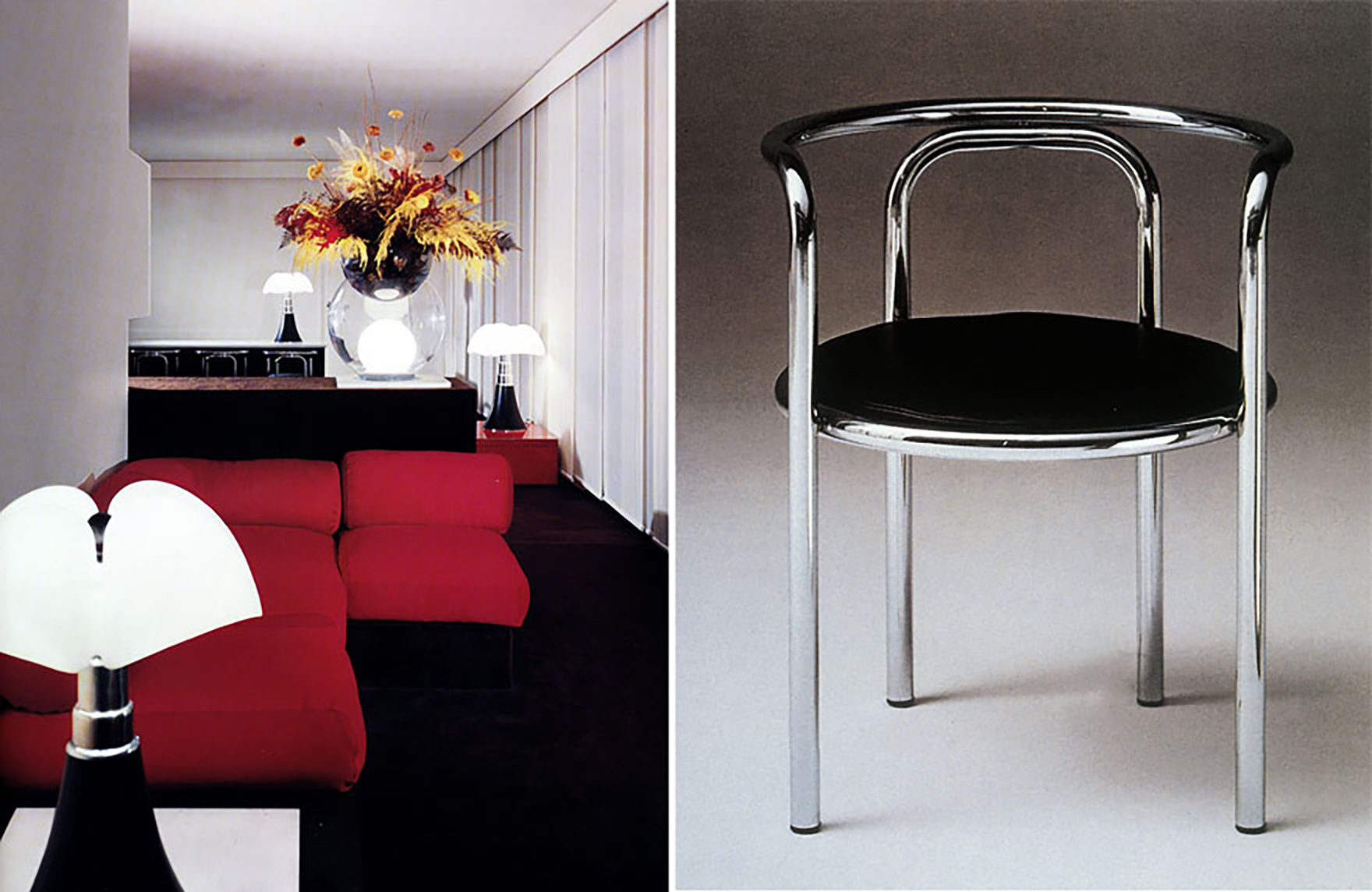

An Aulenti interior in Paris and the Locus Solus chair for Poltronova, both from 1965

An Aulenti interior in Paris and the Locus Solus chair for Poltronova, both from 1965 A 1969 Aulenti interior

A 1969 Aulenti interior The Ruspa desk lamp for Martinelli Luce (1968)

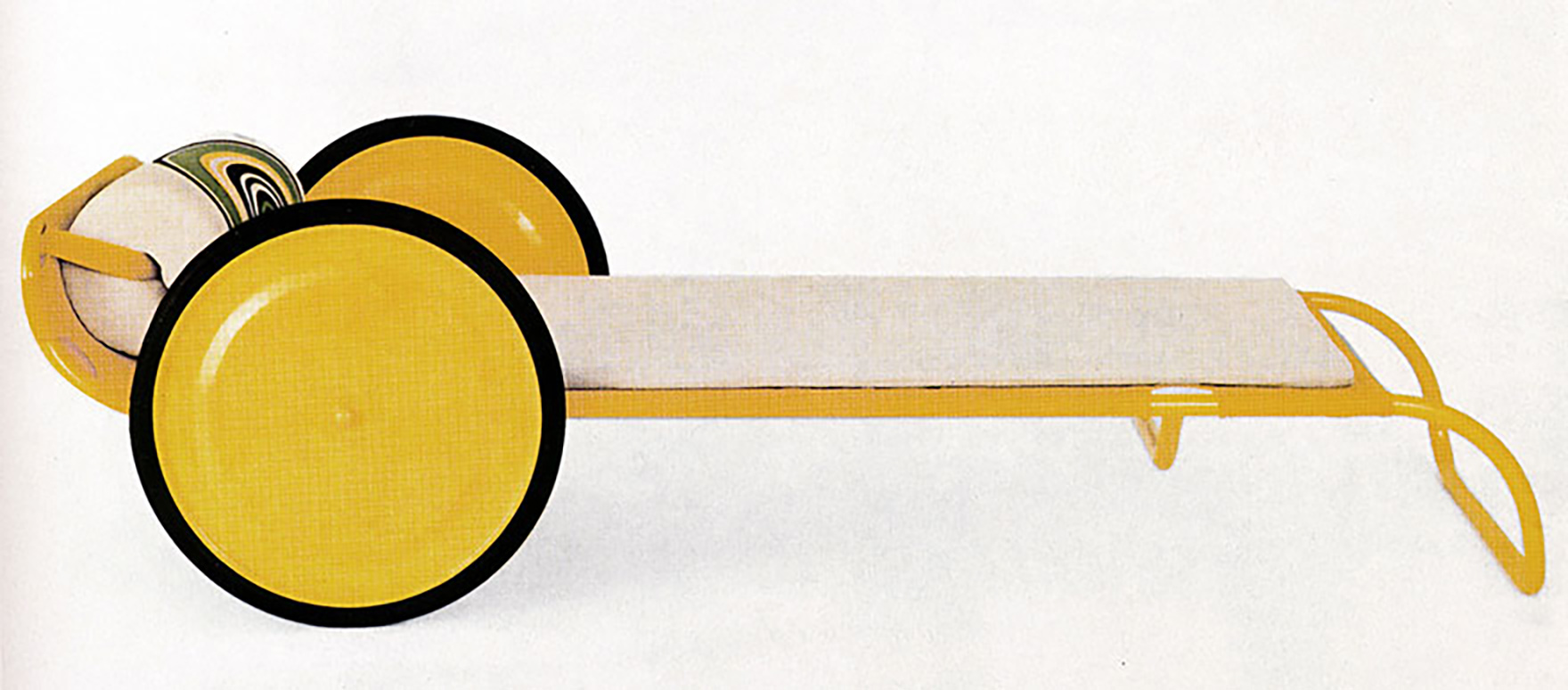

The Ruspa desk lamp for Martinelli Luce (1968) The Locus Solus chaise for Zanotta (1964)

The Locus Solus chaise for Zanotta (1964) Aulenti interiors for the Paris Olivetti showroom, 1966-67

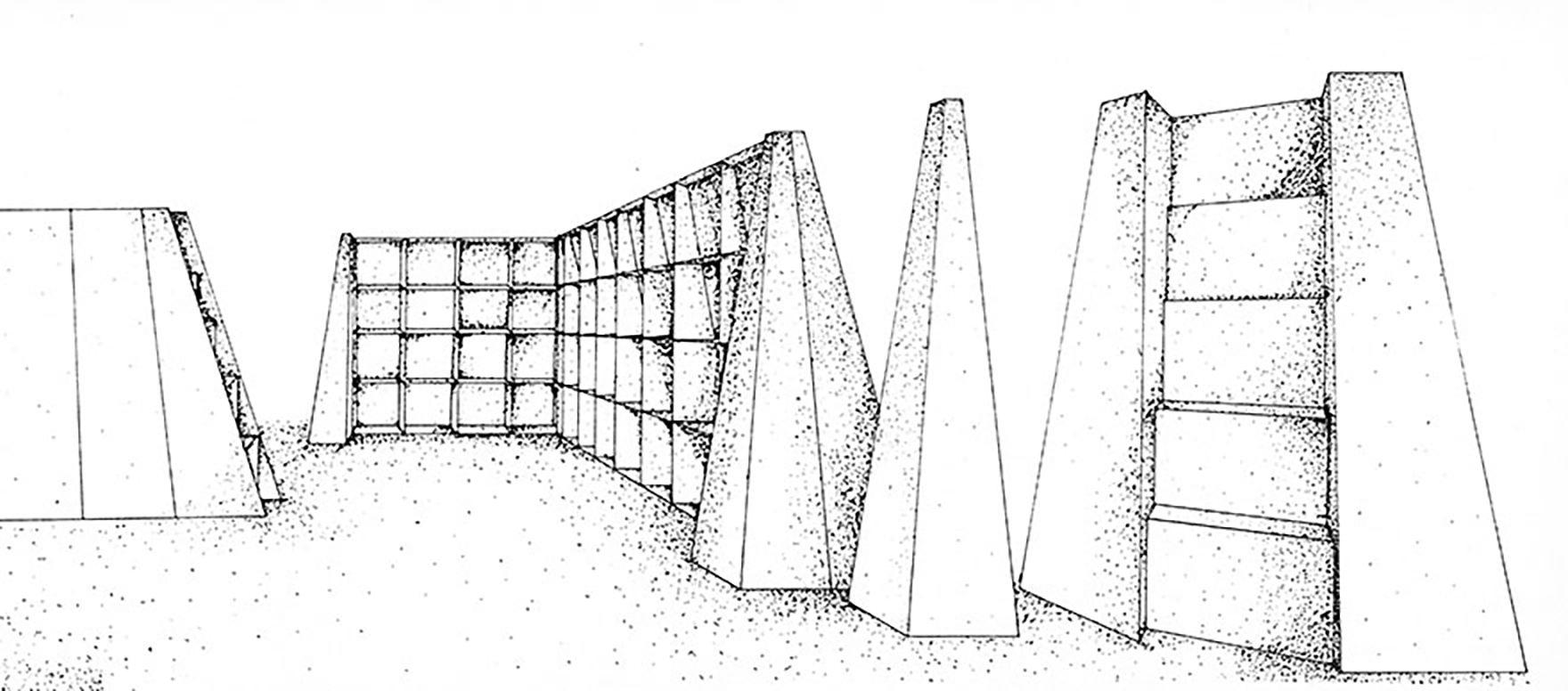

Aulenti interiors for the Paris Olivetti showroom, 1966-67 Drawings for the 1972 exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape at the Museum of Modern Art in New York

Drawings for the 1972 exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape at the Museum of Modern Art in New York Left: the Giova lamp for Fontana Arte (1964). Right: the Patroclo lamp for Artemide (1975)

Left: the Giova lamp for Fontana Arte (1964). Right: the Patroclo lamp for Artemide (1975) More Aulenti lamps for Artemide. Left: Pileo, Mezzopileo and Pileino (1972). Right: Oracolo and Mezzoracolo (1968)

More Aulenti lamps for Artemide. Left: Pileo, Mezzopileo and Pileino (1972). Right: Oracolo and Mezzoracolo (1968) A Poltronova advertisement from 1970 featuring Aulenti's Locus Solus chairs

A Poltronova advertisement from 1970 featuring Aulenti's Locus Solus chairs The Crystal table for Fontana Arte (1982)

The Crystal table for Fontana Arte (1982) Aulenti’s Tavolo Con Ruote table for Fontana Arte (1980)

Aulenti’s Tavolo Con Ruote table for Fontana Arte (1980)— AQQ